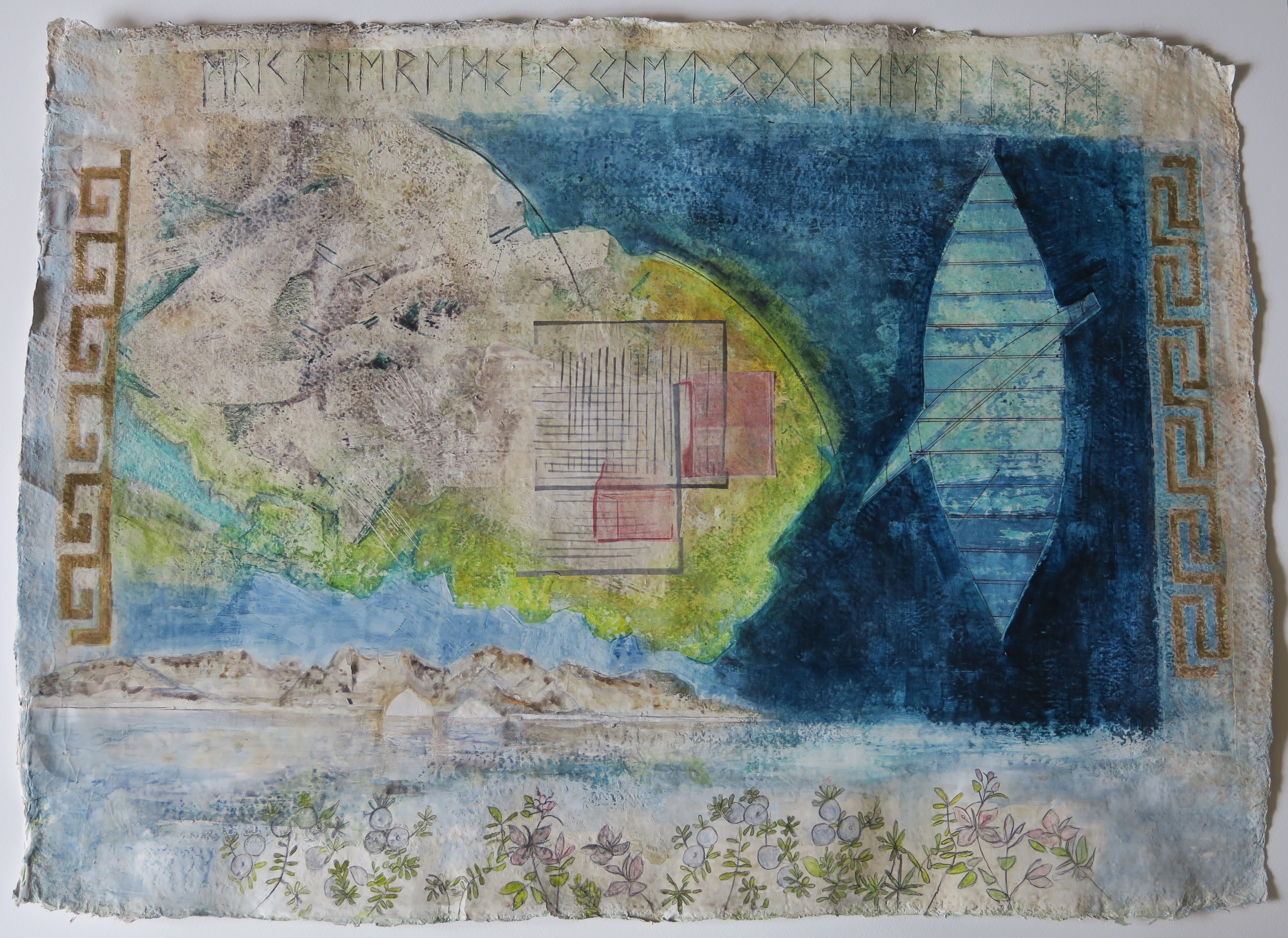

Medieval Warm Period and The Little Ice Age 9th to 19th Century

During the 9th century, when the Vikings were planning their expansion across the North Atlantic, the climate of Northern Europe was far more benign than it is today. This period lasted for several hundred years and was known as the ‘Mediaeval Warm Period’.

Studies of ice cores from Greenland tell us that not only were temperatures relatively mild, but it was much less stormy, particularly during winters. So, for the Vikings and their amazing expeditionary voyages, the North Atlantic was a much more accommodating ocean than it is today and these aspects of weather go a long way to explaining their arrival in Iceland, Greenland and the British Isles during the 9th and 10th centuries.

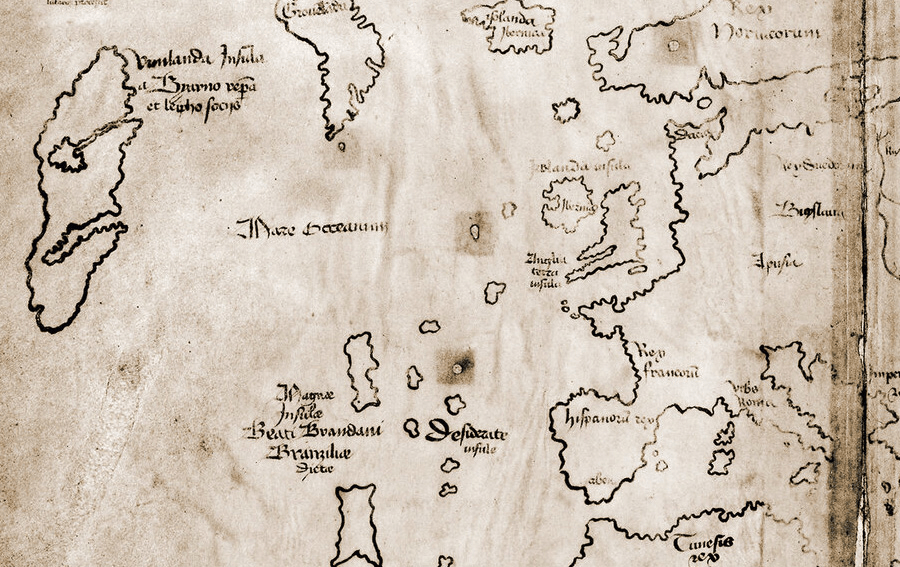

Erik the Red discovers Greenland

Erik the Red having been banished from Iceland and Norway for bad behaviour set sail to find a new land to settle, he spent three years exploring the coast of Greenland looking for places where the land would support him and his family.

But these good times for the Vikings did not last. We know, for example, that the first description of a polar bear in Iceland, from the Viking Sagas, was around the 1250s, hinting at a long-term expansion of sea ice around Greenland and northern Iceland. We also know that in Scotland, the Battle of Largs 1263 marked the end of the Viking occupation of large areas of Scotland. Whether the departure of the Vikings from Scotland was in part related to climate change is a moot point – but weather and climate change may well have had a part to play.

The ’Medieval Warm Period’ was followed by the much more severe climate conditions of the ‘Little Ice Age’, however, the transition was slow and gradual.

From the fragmentary pieces of historical information at our disposal, we know that a pronounced change to much stormier winter conditions did not take place until the 1420s more than 150 years after that first description of the Icelandic polar bear in the Iceland Sagas.

This period of time between the 1260s until the 1420s was complex from the point of view of climate change. For example, historians describe the decade 1300 to 1310 as the time of the ‘Great Rains’. Not only does this time interval include the years before and after Bannockburn1314 but it also coincides with the Scottish military invasion of Ireland in 1315, a military adventure that had a sorry end, as the Scottish soldiers could not cope with the dreadful wet and muddy conditions underfoot – this was followed by a year-long siege of Carrickfergus Castle when starving troops resorted to cannibalism .

15th and 16th Centuries

We do not know much about climate change across Scotland during the 15th and 16th centuries. History books tell us the fine details of political and social change during the Reformation, but there is limited information on the period’s weather and climate conditions. An exception being the huge storms that drove the ships of the Spanish Armada ( returning to Spain in 1588) to the four corners of the British Isles, with many wrecked off the coast of Ireland and Scotland.

To commemorate the defeat of the Spanish Queen Elizabeth , ordered a medal to be minted with an unambiguous inscription:

Circumstances were different for the 17th century.

A handful of diarists provide us with accounts of weather and climate for the 1650s and 1660s.Andrew Hay who lived near Biggar, John Lamont living in Newton ,Fife and John Nicol, writing from Musselburgh, provide us with weekly accounts of weather. John Nicol also gives us details of fine weather that accompanied the harvests during the middle of the 17th century. This tells us that the ‘Little Ice Age’ was not uniformly cold, but that there were brief interludes of sunny and warm weather, particularly during the middle of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

By the later years of the 17th century, winter conditions appear to have been exceptionally cold and snowy, The year 1694 was particularly disastrous, since it was the first of seven years of famine across Scotland known as ‘King William’s Dear Years’. The only known written account of the period, by Hugh Miller from Cromarty tells us a ‘cold east wind accompanied by a dense sulphurous fog ,passed over the country…the land seemed as if struck with barrenness, and such was the change on the climate that the seasons of summer and winter were cold and

gloomy in nearly the same degree’ This time interval spans the 1690s, a time coincident with the early part of the Jacobite uprising, heavy snowfall across the western Highlands and the tragic massacre of the MacDonalds of Glencoe. This appears to have been the coldest part of the ‘Little Ice Age’. Melting snow was frequently associated with major river floods in the Tay, Forth and Spey. Summers were also typically wet leading to crop failures and short growing seasons and famine.

In Scotland after Culloden 1746 life settled somewhat. As ‘The Enlightenment’ flourished during the mid-18th century, attention focussed more on the measurement of Scottish weather and how such information could inform the improvement of everyday life from studies of weather, climate and health, agriculture and safety at sea.

Following the establishment of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, in the 1770s we see the Duke of Buccleuch starting a weather diary for Dalkeith, other detailed diaries containing instrumental weather observation were being undertaken in several estates across Scotland, from Inverness-shire in the north, to Dumfries and Galloway in the south.

For the majority of the 18th century, conditions were cold and snowy, growing seasons were short and spring river flood spates were made more severe as a result of snow melt.

Leave a comment